Sprinters are renowned for their impressive speed and power on the track, but they are equally recognized for their muscular physiques. A sprinter’s physique is one that many people aspire to achieve, especially those who find the bodybuilding look to be too unnatural.

There are a number of misconceptions about how track and field sprinters attain that muscular look.

A common narrative is that it is the sprinting itself that results in that particular physique. You’ll often hear people cite the differences between a marathon runner’s body and a sprinter’s. If there is such a dramatic difference between the two, surely it has something to do with the running style.

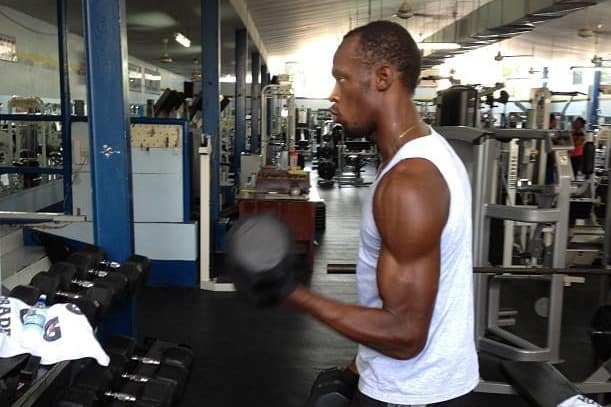

In reality, sprinters achieve their muscular physiques mainly through weightlifting done to supplement their running workouts. The fast-twitch nature of sprinting helps, but it is mainly the strength training that results in muscle gain.

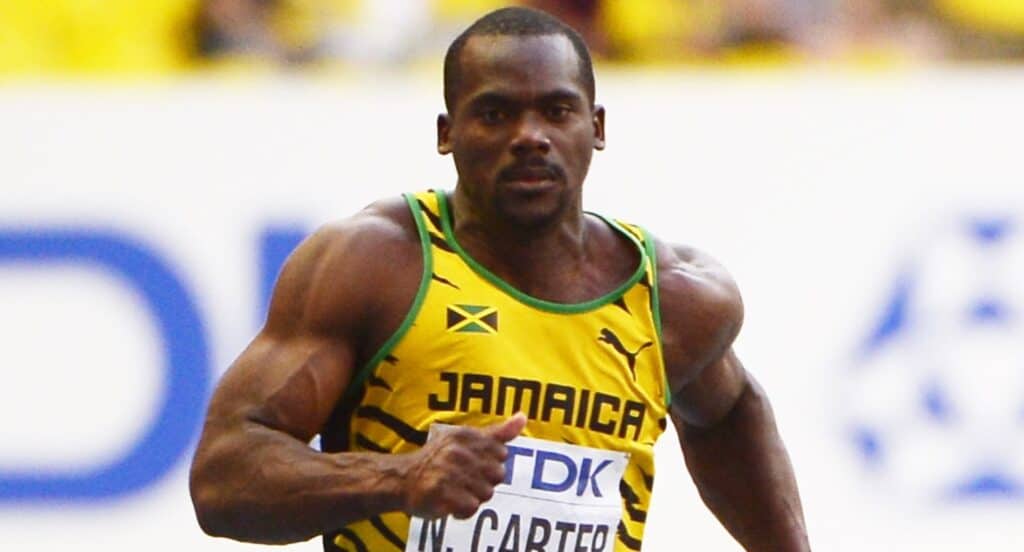

While every sprinter is lean, there is a wide range of muscularity among them. Nesta Carter looks like an NFL running back. Usain Bolt, while certainly muscular, has a more athletic look.

Misconceptions About Sprinting and Muscle Gain

It is often believed that the intense and explosive nature of sprinting is enough to build muscle and create the impressive physiques seen on the track. However, this is not entirely accurate. While sprinting does contribute to muscle gain, it is mainly the weightlifting and strength training done by sprinters that result in the muscular development we see.

All of the top track sprinters incorporate strength and conditioning into their routines. Usain Bolt’s lifting routine consisted of hang cleans, weighted step-ups, and tons of core work. Asafa Powell used box squats and other Olympic lifts in his training. Even going back to Ben Johnson, who squatted upwards of 500lbs.

When comparing the physiques of marathon runners and sprinters, it’s important to note that lifting weights is not a part of most marathon running programs.

Sprinting, particularly events like the 100 meters and 200 meters, is highly anaerobic. Lifting weights is also anaerobic and complements sprinting performance.

A marathon runner may lift weights, but their bodies do not create the environment for muscle gain with all of the aerobic activity. A phenomenon known as the “interference effect” has a negative impact on muscle gain.

When you engage in long-duration, low-to-moderate intensity cardio, the body releases an enzyme called AMP-kinase (AMPK). AMPK signals the body to break down substrates to be used for fuel. This makes sense when you consider the high energy demands for this type of long-distance cardio.

The “problem” is that AMPK inhibits the body’s ability to build muscle. So even if a marathon runner wanted to put on size, they would be limited.

The Role of Weightlifting in a Sprinter’s Training

While sprinting itself certainly contributes to muscle gain, weightlifting provides the targeted resistance training needed to build and shape specific muscle groups.

Sprinters typically use lower-body compound exercises like squats and Romanian deadlifts, while occasionally mixing in isolation movements to address specific weaknesses.

Explosive exercises like power cleans and snatches build strength, but more importantly power throughout their bodies. These exercises help to develop the fast-twitch muscle fibers that are critical to sprinting success, allowing athletes to generate force at the snap of a finger (or a gunshot on the starting blocks).

Of course, weightlifting isn’t just about building muscle mass – it also plays a key role in injury prevention and overall athletic performance. Strengthening the posterior chain, particularly the hamstrings for sprinters, is one of the best ways to prevent knee injuries.

The Impact of Genetics on Sprinters’ Muscular Development

Some people are simply more predisposed to building muscle than others. This is due to a number of genetic factors like hormone levels and muscle fiber composition. For example, individuals with a higher percentage of fast-twitch muscle fibers tend to have greater potential for explosive power and strength. This translates well to sprinting and other explosive sports like football.

However, recent research has shown that muscle fiber type is not a static thing. Muscle fiber type can be changed with specific training. Anaerobic training will make you more fast twitch, while aerobic training will make you more slow twitch.

In addition, muscle fibers fall on a spectrum rather than being definitively one or the other.

With all of that said, genetics do play a large role in where your physique gravitates. As you have probably noticed, some people are naturally skinny and are “hard gainers”, while others seemingly put on muscle just by looking at a rack of dumbbells.

This doesn’t mean that genetics is the only factor in determining an athlete’s success. At the highest level, where everyone is gifted, it is the most disciplined athletes that become champions. However, it’s important to recognize that some individuals may have a natural advantage when it comes to building muscle and excelling in explosive sports like sprinting.

Performance-Enhancing Drugs and Sprinters’ Muscular Development

Now to address the elephant in the room when it comes to the impressive physiques among elite sprinters.

While resistance training and genetics play a significant role in the development of sprinters’ physiques, it’s important to acknowledge that some athletes may turn to performance-enhancing drugs (PEDs) in order to gain an edge.

Sprinters use PEDs to improve track performance and workout recovery. PEDs can also reduce the risk of injury or enhance recovery from injury. While the use of PEDs is prohibited in many sports, including track and field, some athletes are willing to take the risk.

Even though sprinters use PEDs for the performance benefit, physique development is a natural byproduct. Anabolic steroids can help with both muscle growth and fat loss. When you are already an athlete at the highest level, that effect can be exponentially greater than the average person.

In addition to potential PED use, some sprinters also use natural dietary supplements to improve their performance and recovery.