Flexible dieting, or if it fits your macros (IIFYM), rose in popularity in the late 2000’s particularly on the bodybuilding.com nutrition forums. The acronym IIFYM was coined on that forum and later endorsed by well respected fitness researchers like Alan Aragon and Layne Norton.

On that forum, people would commonly ask if they could eat certain foods like pretzels, white bread, or peanut butter on a diet. These are foods that weren’t overtly “healthy”, which lead people to question whether they were allowed while cutting body fat. The standard reply was always that you could eat these foods so long as they fit your macros.

The premise was that the overall structure of the diet is more important than the inclusion or exclusion of certain foods.

What is Flexible Dieting?

Flexible dieting is an approach in which no foods are off limits, and the focus of the diet is on hitting daily macronutrient targets based on your physique, activity levels, and goals. Unlike elimination diets like paleo, keto, or veganism, flexible dieting gives individuals the freedom to eat any food they want with these macronutrient targets in mind.

The three main macronutrients are protein, carbohydrates, and fats. Protein rebuilds muscle and other tissues, and provides immune system support. Carbohydrates are the primary energy source for most physical activity, including exercise. Fats are a reserve energy source and support healthy hormone levels. Since these are macronutrients as opposed to micronutrients like vitamins and minerals, they are measured in grams.

Flexible dieting came about in opposition to the idea of clean eating, a term used to describe a finite number of foods that are permitted on a diet. These are things like chicken breast, broccoli, egg whites, tilapia, and brown rice. Flexible dieting was proof that you could still get into shape, even bodybuilding competition shape, by going beyond this scope of common dieting foods.

The issue with the idea of clean eating or clean foods was that the definition of healthy vs. unhealthy gets blurry when certain foods are discussed. Most would agree that vegetables are healthy and fast food is unhealthy, but bring up something like fruits and you’d get a wide variety of responses.

“Fruit is unhealthy, it’s loaded with sugar”

“Fruit is healthy; it’s a great source of vitamins, minerals, and fiber.”

Here lies the problem with black and white thinking and labeling foods as unequivocally good or bad. These arguments about specific foods lack the context of an individual person’s situation. The benefit of flexible dieting is that each person can make their own decision about what they want to include in their diet, as opposed to following arbitrary rules found in some diet book.

Does Flexible Dieting Work?

While no dieting protocol is perfect, flexible dieting has numerous benefits that other diets cannot claim. The first is that an individual will learn the nutritional content of a multitude of different foods.

The best comparison to flexible dieting is that of a personal financial budget. If a person makes $70,000 per year, could they purchase a $40,000 sports car? They could, but they would have to make major sacrifices in other aspects of their life like housing, vacations, and entertainment. This same principle applies to flexible dieting.

IIFYM enables someone to weigh and track their food daily. Over time they will learn the calorie and macronutrient content of a variety of foods. They will then discover which foods are worth it or not worth it to consume on a regular basis.

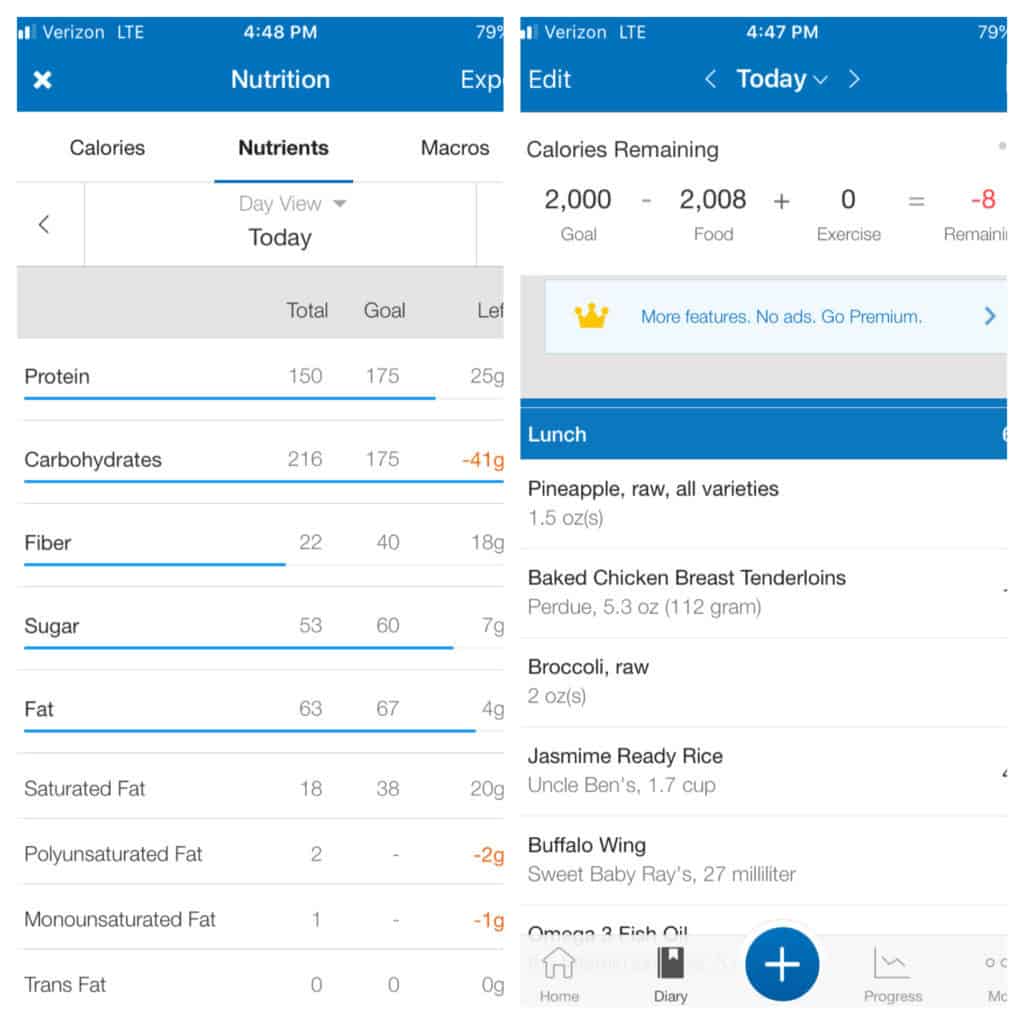

Working back to the budget analogy; let’s say a person is on a diet and has a target of 2,000 calories per day, with a macronutrient split of 175g of protein, 175g of carbs, and 67g of fat.

Could they fit a few slices of pizza into their diet? Sure, but that would take a massive chunk out of their carbohydrates and fats. There would need to be considerable adjustments for the remaining meals. It would basically be protein shakes and grilled chicken salads. Once in awhile this is okay, but in the long run it would likely be problematic. It would be very hard to adhere to such a strict eating regimen consistently.

In the end however, it’s a learning experience. They now realize just how calorically dense certain foods are. But at the same time, they’re not off limits. It teaches people how to have balance in their lives while still taking steps toward their physique goals.

The pizza example given was also of a person on a cutting phase looking to lose weight. Someone bulking or even at maintenance would have more leeway with their macros and calories. As a result, they could enjoy a wide variety of foods without as much sacrifice.

Another benefit of flexible dieting is that it’s applicable for all dietary goals; gaining muscle, losing fat, improving athletic performance, and general health improvements. You would simply have to choose the appropriate calorie and macronutrient split for your particular goal.

How to Calculate Your Macros

There are a number of variables that go into calculating your macros, including age, body fat level, activity level, gender, and weight. Luckily there are numerous calculators online that will give you an estimate of how much you should be eating.

But before you can calculate your macros for a specific goal, you must calculate the number of total calories you should be eating each day to maintain your weight.

Total daily energy expenditure, or TDEE, is a combination of basal metabolic rate, non exercise activity thermogenesis (NEAT), thermic effect of food (TEF), and exercise activity. These four factors give you the total number of calories you should consume each day.

Basal metabolic rate is often referred to as “the number of calories you would burn in a coma.” Believe it or not, even when you’re doing absolutely nothing, you’re burning quite a few calories. It takes energy to keep your organs functioning, your heart beating, and your brain firing. All of these internal bodily processes factor into basal metabolic rate, or BMR.

Non exercise activity thermogenesis is best defined as activity that is not formal exercise. Walking to your car, fidgeting at your desk, and doing household chores are examples of NEAT.

Breaking down food in the body also requires energy. This is known as the thermic effect of food. Each food category requires a certain level of energy (calorie burn) to digest and absorb. Protein and fiber rank highest in TEF, while carbohydrates and fats are lower.

If you type TDEE Calculator into a google search, you will get a variety of results. Each calculator uses a slightly different formula to spit out a daily caloric goal. In my experience, I’ve found that most of these calculators overestimate the number of calories you need. So it’s best to type your information into multiple calculators and take the average, but also err on the low end of the spectrum.

Another drawback of TDEE calculators is their interpretation of activity level. Often they will give guidelines on which activity level to choose, but they will be based on a person’s occupation. For example, they may say to choose “moderately active” if you’re on your feet for most of the day at your job.

However, many people work sedentary jobs but will hit the gym for over an hour up to six days per week. It can be confusing for the user to determine where they fall on the all important activity factor. Luckily there is a simple mathematical formula to calculate TDEE yourself.

Let’s use the example of a 180lb healthy male (but this works for females as well).

First take your weight and multiple it by 10. This will give a rough estimate of your BMR.

180 x 10 = 1800 calories from BMR

Then take this number and multiply it by an activity coefficient. This encompasses both exercise and NEAT. The activity coefficient ranges from 1.3-2.3, but can be even lower or higher in rare circumstances.

| Activity Level | Description |

| 1.3 – 1.4 | Sedentary job and sedentary lifestyle |

| 1.5 | Sedentary job and 3 workouts per week Active job and no additional exercise |

| 1.6 – 1.7 | Sedentary job and 5 workouts per week Active job and 2-3 workouts per week |

| 1.8-1.9 | Sedentary job and 6-7 workouts per week Active job and 4-5 workouts per week |

| 2.0-2.3 | College/pro athlete training level, multiple workouts per day |

Let’s say this individual has a desk job, but still works out hard 5 days per week. They would probably fall in the 1.6-1.7 range.

1800 x 1.6 = 2880 calories per day

Now that we have an estimate of our maintenance calories, we can break this down into individual macronutrients. When calculating macros, always start with protein. Protein is unique since it is the only macronutrient that can build and repair tissue, such as muscle. Carbohydrates and fats are relatively interchangeable, but nothing can replace protein.

An easy rule for protein is to consume 1g per pound of bodyweight. This works for most people, but if you are overweight or obese you can consume 1g per pound of lean body mass or 1g per pound of your target healthy weight. If you are at a healthy weight and want to consume more than 1g per pound that is fine as well. Studies have shown favorable physique benefits for people who consume above this level of protein with no deleterious health effects.

This 180lb individual would consume 180g of protein per day.

Since protein is 4 calories per gram, protein would take up 720 calories of their diet (180×4). This leaves us with 2160 calories to work with between carbs and fats (2880-720).

As mentioned, carbs and fats are relatively interchangeable. As long as you’re not going to extremes (i.e. consuming no fat and all carbs or vice versa) you have quite a bit of liberty to choose based on your personal eating habits.

Do you have a preference for foods high in carbohydrates, such as whole grains, fruits, or starches? Place a greater proportion of your calories to carbs.

Do you prefer fats, such as nuts, avocados, and fatty meats? Place a greater proportion of your calories to fats.

If you want to play it by the book, another rule of thumb is to multiply your bodyweight by 0.4 to determine the total grams of fat you should consume each day. After that you would consume the remainder of your calories from carbs. In our example:

180 x 0.4 = 72g of fat per day.

Since fat is 9 calories per gram, fats would make up 648 calories of their diet (72×9). This leaves us with 1512 calories to use on carbs (2160-648).

Like protein, carbohydrates are 4 calories per gram. Since we have 1512 calories remaining:

1512/4 = 378g of carbs per day

In conclusion, the calorie and macronutrient targets for a 180lb male with a sedentary job who works out 5 days per week would be approximately:

| Calories | 2880 |

| Protein | 180g |

| Carbohydrates | 378g |

| Fat | 72g |

Remember this is only an estimation and that this is for maintenance calories, meaning the calories they would consume to maintain their body weight. If you wanted to bulk up you would increase the calories, and if you wanted to lean out you would decrease the calories.

When trying to lose fat, protein should still remain at 1g per pound or higher, since preserving muscle is very important on a cut.

There is trial and error involved in picking the right calorie and macronutrient totals, but this is a great start to get things going. It’s important to find your maintenance levels first even if your ultimate goal is to gain/lose weight. Otherwise you’d just be arbitrarily choosing random numbers.

The easiest way to determine if the maintenance calories/macros are accurate is to eat those amounts and weigh yourself daily for about a week or two. If your weight remains relatively the same (water fluctuations will always cause some changes), you’re likely on the right path.

Choosing What Foods to Eat

The main perk of flexible dieting is that no foods are forbidden. But it doesn’t mean you should eat junk haphazardly with no regard for nutrition. The people who pound protein shakes for breakfast and lunch so that they can gorge on pizza and ice cream at night are what give IIFYM a bad name.

The diet isn’t about fitting junk foods in every day just because you can; it’s about having the liberty to do so if situations call for it. With flexible dieting, you can attend social gatherings without guilt or having to stray from your macros. You can have a few donuts or some chips once in awhile just because you’re in the mood.

You’ll often hear people reference the 80/20 rule or 90/10 rule when talking about dieting. This means that 80% of your calories should come from minimally processed, nutrient dense, whole foods, while the other 20% can come from less nutritious sources.

What people discover when implementing IIFYM is that some foods just aren’t worth it in certain situations. This is particularly the case during dieting phases when carbohydrate and fat macros get lower. This is often affectionately referred to as “poverty macros.”

Could you fit a bag of skittles in your diet if your carbohydrate macros are 150g? Yes, but it may not be worth it. The skittles aren’t particularly satiating, and may leave you hungrier than when you started due to the blood sugar response. Once in a while you may do it for fun, but strategically it’s probably best to avoid it.

This depends on your personality as well. I’m not the type of person to have a few scoops of ice cream; I’ll want the whole pint. For me, trying to fit this into my macros would require more willpower than just avoiding it completely.

On the other hand, there are people that can have a handful of m&ms and be totally fine. A small amount was enough to satisfy their sugar craving. Neither approach is right or wrong, it’s just about putting yourself in a position to succeed long term.

If you’re bulking on 500g of carbs per day it’s a completely different story. At that level of carbs, it actually becomes difficult to hit that number with strictly healthy foods like oats, potatoes, and vegetables. The candy may be a welcome treat if they’re constantly stuffed from fibrous and dense food choices. These examples are why context is so important when choosing foods.

In the end, nutritious whole foods are the way to go for the bulk of your diet. My thought is that if you’re going through the trouble of weighing and tracking your food, you might as well be eating the best food sources possible. This is similar to the Stan Efferding ‘Vertical Diet’, where the diet is based on nutrient dense and/or easily digestible foods while still taking macros into consideration.

Tools Needed to Get Started

Nowadays there are a variety of food tracking apps that help you keep a running food diary while tracking macros. MyFitnessPal is the most popular, along with others like MyPlate and Lose It. They even have barcode scanners with a huge database of packaged goods so that you don’t have to input the macros in manually.

They all have their pros and cons, with most people choosing one that has an interface to their liking. Just remember to input your personal calorie and macronutrient goals manually, as some of them will give you their own arbitrary (and usually woefully inaccurate) macros. Also keep in mind that these apps aren’t perfect; the food database is often user created so the numbers may be off.

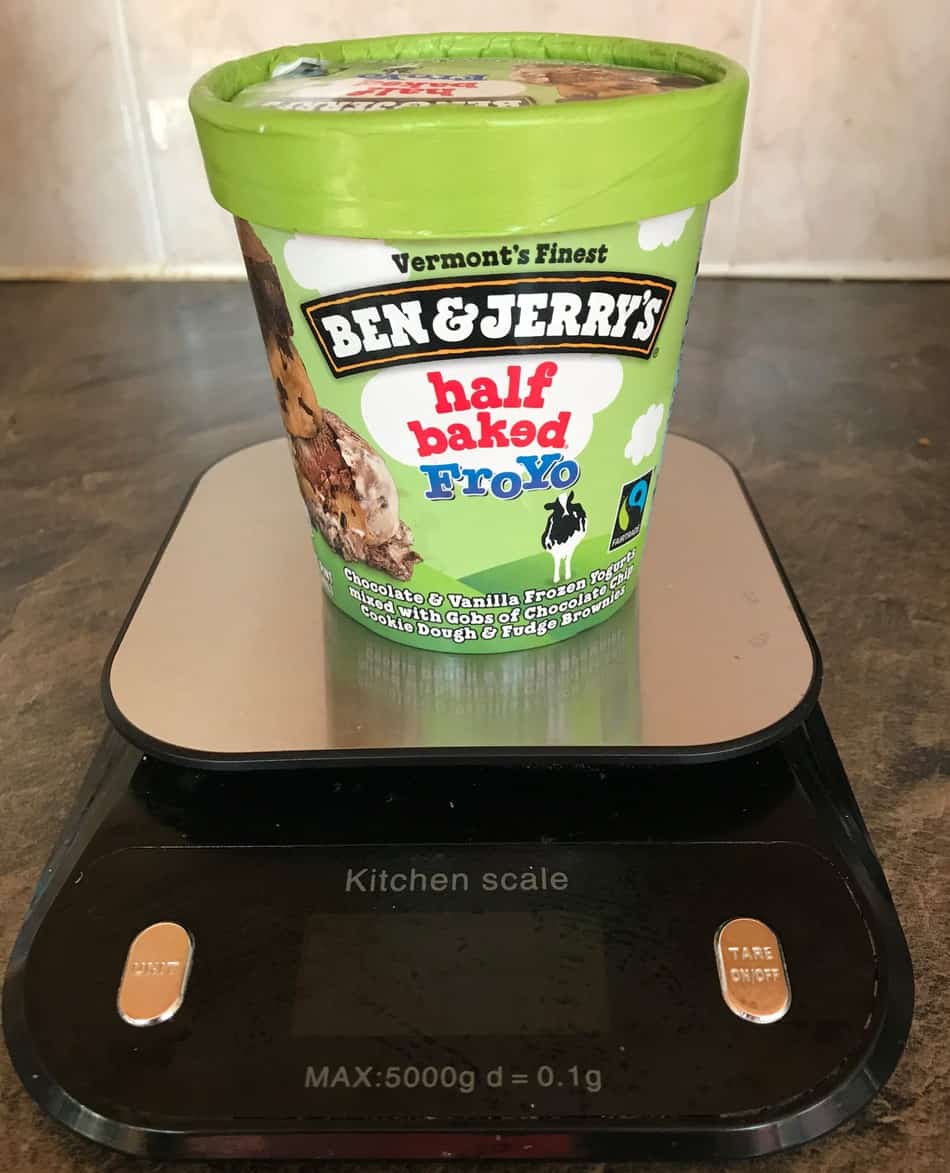

In order to measure food properly, you’ll need a food scale and measuring cups. With nutrition clients I cannot recommend this enough. It would be such a shame to go through all the trouble of setting up a diet and buying food, only for everything to be wrong because it wasn’t measured properly. It’s tedious but it must be done, particularly in the beginning. Over time you’ll get better at eyeballing food measurements, but better safe than sorry in the initial stages.

Drawbacks of IIFYM

There is a learning curve when someone tracks their macros for the first time. In all likelihood they don’t have much knowledge of the nutritional makeup of specific foods. As helpful as it is to plan out your day in advance, things happen. Situations come up where you miss a meal, forget to take food out of the freezer, etc.

When this happens you have to think on the fly and in some cases your macros will be off for that day. Over time however, transitioning from a planned meal to something different becomes seamless.

IIFYM also requires a great deal of self reliance. This is not a tell me what to eat and I’ll eat it diet. It requires planning and to a certain extent, creativity.

But that is the point. If people blindly follow instructions, they don’t learn about nutrition nor make real behavioral changes. Those diets typically are not sustainable either. If after all of this you say flexible dieting isn’t for you, at the very least you can say you learned a great deal about nutrition.

Flexible dieting isn’t about fitting as many junk foods into your diet as possible, it’s about having the freedom to do so. You may not even choose to use that freedom. But having that option is often enough to improve adherence.